Alma-Ata 40 years on

On by Sorsha Roberts

It is time to renew and reaffirm the Alma-Ata principles

This week the World Health Organisation – along with governments, other global institutions, and civil society groups– are celebrating the 40thanniversary of the Alma-Ata Declaration on Primary Health Care. This is a genuinely significant event for everyone who cares about the Right to Health. The Alma-Ata Declaration was a watershed moment in global health, and it continues to nourish and inspire social movements around the world due to its positive, holistic and radical approach to health.

Health Poverty Action was set up shortly after the Alma-Ata conference, motivated by the vision of ‘Health for All by the year 2000’, and driven by the four core Alma-Ata Principles:

- Justice-oriented approach: Health justice cannot be achieved without social and economic justice.

- Strong community roots: The Alma-Ata Principles emphasise the importance of accountability and community participation in health care.

- Comprehensive health systems: The principles call for a comprehensive and integrated approach (as opposed to concentrating on selective vertical interventions).

- Social determinants of health: They call for a coordinated multi-sector approach, emphasising health cannot be achieved without addressing factors such as poverty, discrimination and inadequate access to key health determinants such as food, water/sanitation, and education.

40 years on, the truth is that there really isn’t an awful lot to celebrate. Of course, some progress has been made, but as the official Astana Declaration recognises, we are far from achieving the goal of ‘Health for All’:

Over half of the world’s population, especially marginalized communities, cannot access essential health care. Where communities do have access to services, care is too often inappropriate or unsafe. Around the world, 100 million people are driven into poverty each year because of out-of-pocket spending on health services.

Moreover, even where improved health outcomes have been achieved, they are unevenly distributed, and in some places are being reversed.

The fundamental reason for this lack of progress is the rejection by governments – primarily, governments in the Global North – of the Alma-Ata principles. In particular, one of the most exciting, and far-reaching elements of the Alma-Ata declaration was the call for a ‘New International Economic Order’, which was necessary to secure ‘the fullest attainment of health for all and […] the reduction of the gap between the health status of the developing and developed countries’. But what we have in fact seen is the precise opposite: the expansion and near-dominance of neoliberalism.

This becomes clear when we compare the Alma Ata 40 declaration released this week with the original declaration. Gone are the calls for a New International Economic Order and reducing gap between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have-nots’, and gone are the calls for reduced spending on the military. Whilst the draft Alma Ata 40 does reaffirm its commitment to Primary Health Care, which is to be applauded, it does so in the context of achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Universal Health Coverage (UHC) 2030 agenda, which themselves have been subject to criticism for failing to take account of the very imbalances of power that are fundamental to the analysis underpinning the original Alma Ata declaration.

The original Alma-Ata declaration provided a rigorous and inspiring agenda for achieving ‘health for all’. The fact that we have made such poor progress towards that goal is not a reason for diluting the Alma-Ata principles, but rather for re-affirming them and, crucially, this time demonstrating a genuine political commitment to implementing them.

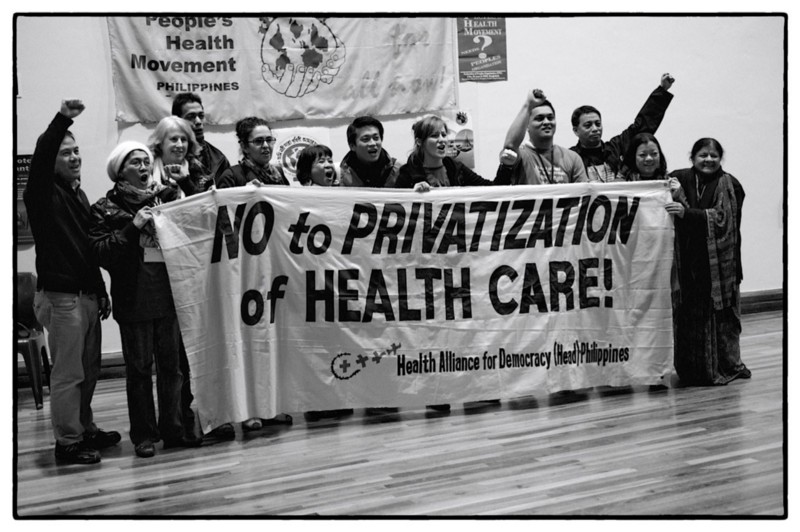

To learn more, read our blog written with the People’s Health Movement.